In the last issue, we explored the incredible world of our second brain—the gut microbiome. We covered:

- How this vast biological system works

- How much the gut influences our health

- The gut–brain connection

- Warning signs of microbial imbalance

- Strategies to support a balanced microbiome

Missed it? You can still catch up on Part 1 of The Microbiome Issue.

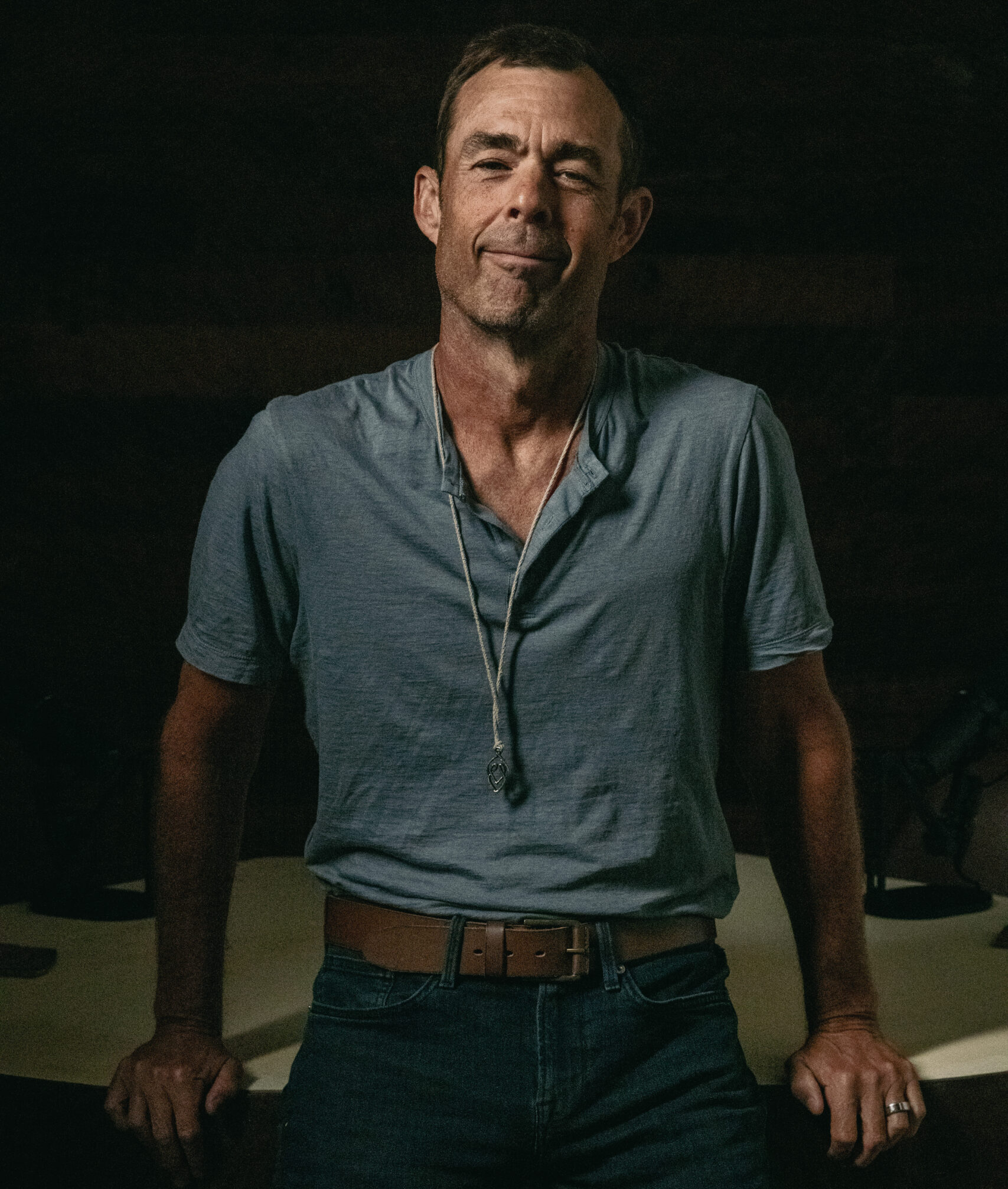

But the more learned, the more questions we had. Fortunately, we have the perfect expert to help. We took your most pressing questions to Dr. Mahmoud A. Ghannoum—the world’s leading gut microbiome researcher (according to the Washington Post)—for a gut check.

Dr. Ghannoum isn’t just a microbiome expert—he’s the scientist who named the human mycobiome (the fungal side of our microbiome). Last year, Dr. Ghannoum was recognized among the top 1% of scientists for Citation, as his work has been cited over 47,000 times in medical literature. A professor at Case Western Reserve University and a leading researcher in medical mycology, he has published over 550 peer-reviewed papers and written six scientific books.

As the co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer of BIOHM Health, Dr. Ghannoum helped develop the BIOHM Gut Test, one of the most advanced at-home tests giving people unprecedented insight into their microbiome. He was also a featured speaker at the inaugural Eudemonia Summit, sharing his expertise on the critical role the microbiome plays in longevity and optimal well-being. With degrees spanning medicinal chemistry, microbial physiology, and business, Dr. Ghannoum has reshaped how we think about gut health.

QUESTION 1: WHY DO I OFTEN EXPERIENCE BLOATING, GAS, OR CONSTIPATION WHEN I TRAVEL?

When traveling, having the uncomfortable feeling of being bloated, sluggish, or constipated happens to more of us than we think. Even if our diet stays the same, changes in air pressure, stress, sleep, and hydration can all wreak havoc on our digestive system.

Changes in Air Pressure

When we’re up in the air, the drop in cabin pressure causes gases in the digestive system to expand, thus causing bloating and discomfort.1 Even the usual gas produced by our gut microbes suddenly takes up more space, making bloating and distension feel more intense than usual.

Stress

In general, our gut feels our stress, too. Sometimes, traveling causes us extra stress and anxiety. Navigating airports and directions, putting up with flight delays and cancelations, and the anxiety brought about by COVID makes us weary and on high alert when fellow passengers sneeze.

Sleep

Moreover, changing time zones and even the beds and pillows in the hotels in which we stay can lead to disrupted sleep. Since the gut and the brain are in constant communication (the gut–brain axis), stress and anxiety can disrupt our gut balance, leading to constipation and bloating.2

Hydration

Hydration is also a major factor. Airplane cabins are notoriously dry, and dehydration is a major trigger for constipation. Even small shifts in our routine—like drinking less water or eating fewer fiber-rich foods—can pose temporary challenges to our digestive system.

To minimize these digestive discomforts, maintaining proper hydration, managing stress, and being mindful of dietary choices can be beneficial. Following a low- fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet—which limits fermentable carbohydrates known to contribute to bloating—may help reduce symptoms. In addition, incorporating fiber-rich foods or supplements, as well as magnesium, can prevent travel-related constipation and support regular bowel movements. Ensuring adequate sleep and engaging in light physical activity, such as walking, can also help maintain gut motility.

QUESTION 2: ARE THERE SPECIFIC STRAINS OF PROBIOTICS THAT HELP WITH IBS, SIBO, OR IBS?

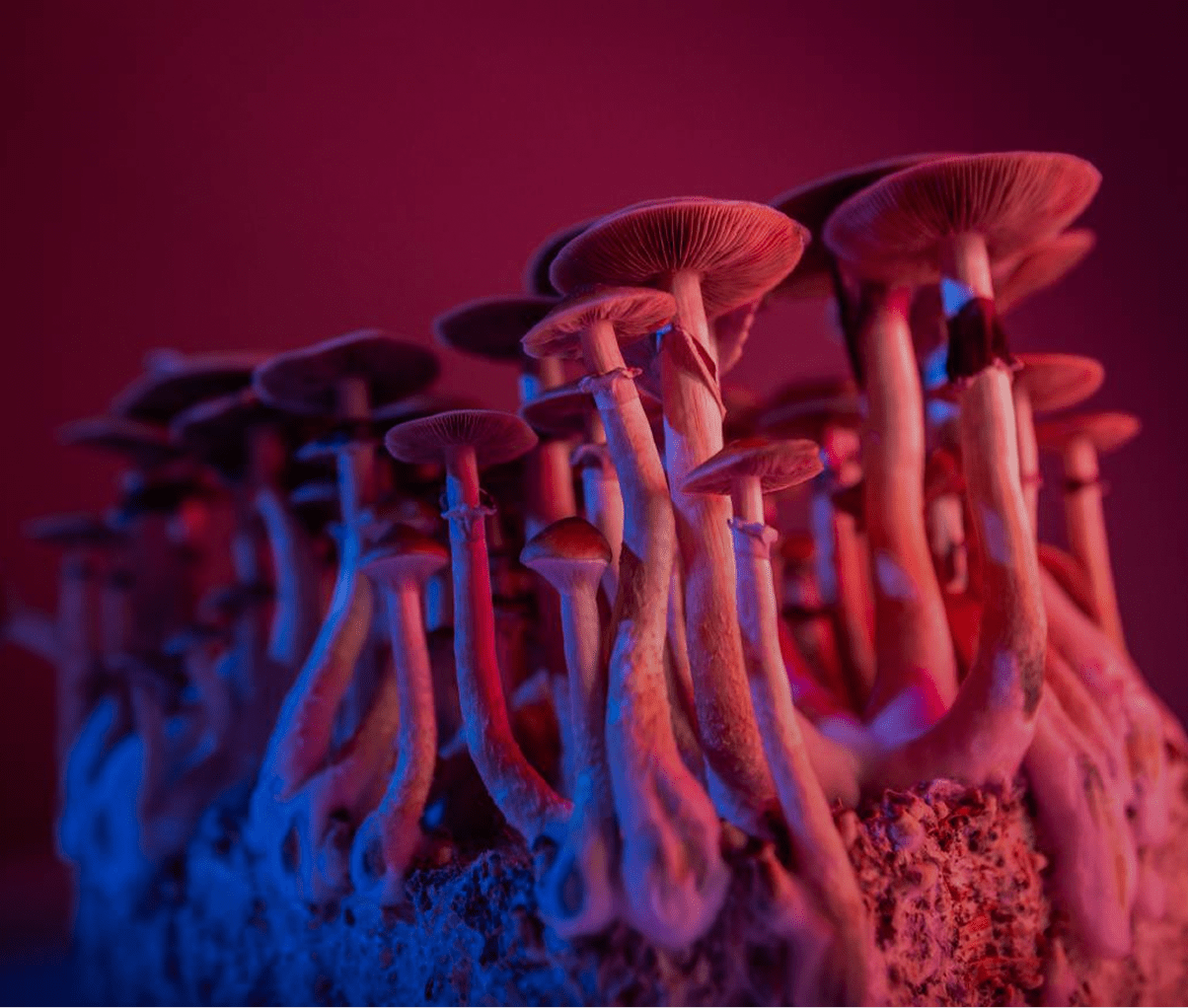

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) are well-recognized conditions linked to gut dysfunction. Each has distinct underlying causes and clinical presentations, requiring tailored, personalized approaches to restoring microbial balance. However, Small Intestinal Fungal Overgrowth (SIFO) is often overlooked despite its significant role in gut dysfunction. In fact, Jacobs et al. previously showed that about 34% of patients with SIBO also have SIFO.3 Addressing SIFO alongside other known conditions is crucial.

At the core of these conditions is dysbiosis, a microbial imbalance that fuels symptoms and disease progression. One complicating factor is the formation of biofilms—protective matrices formed by bacteria and fungi that shield the harmful microbes from the immune system and antimicrobial treatments—which makes infections more persistent. These biofilms (known as Digestive plagues) need to be addressed to improve the gastrointestinal symptoms encountered as a result of dysbiosis.4

Probiotics play a key role when it comes to rebalancing the gut. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains are widely used to support digestion, improve gut motility, and regulate inflammation. These probiotics can help restore beneficial bacteria, which is especially useful for individuals with IBS and IBD.

Saccharomyces boulardii, a known probiotic yeast, is particularly beneficial in cases of SIFO, as it helps balance fungal populations—particularly Candida—reduce polymicrobial (bacteria and fungi) biofilm formation, and support overall microbiome health. In SIBO, however, some studies suggest that probiotics should be chosen carefully, as they may contribute to an overgrowth of methanogenic bacteria such as Methanobrevibacter smithii that can potentially exacerbate symptoms like bloating and constipation. This example highlights the importance of a personalized approach to probiotic selection in order to prevent unintentional microbial imbalances.5

Additionally, incorporating digestive enzymes such as amylase, can be useful across these conditions. Amylase helps break down harmful digestive biofilms in the gut lining, disrupting the protective matrix that bacteria and fungi use to evade the immune system and antimicrobial treatments.6 By enhancing carbohydrate breakdown, amylase also reduces undigested food particles that fuel fermentation, bloating, and microbial growth. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals with SIFO and SIBO, where excess fermentation contributes to symptoms, as well as for those with IBS and IBD who often struggle with malabsorption and inflammation.

While probiotics and digestive enzymes play an essential role in gut health, they should be part of a comprehensive strategy that includes dietary modifications and lifestyle management (e.g. exercise, stress management, meditation, etc.) to promote a well-balanced microbiome and long-term digestive wellness.

QUESTION 3: HOW DOES GUT MICROBIOME COMPOSITION CHANGE WITH AGE - AND ARE THERE SPECIFIC INTERVENTIONS TO SLOW OR REVERSE NEGATIVE SHIFTS?

The gut microbiome is a dynamic ecosystem that evolves throughout life, with significant shifts occurring from infancy to old age. In early life, the gut is rapidly colonized by beneficial bacteria, largely influenced by birth method, breastfeeding, and environmental exposures. During adulthood, the microbiome stabilizes. But as we age, microbial diversity tends to decline, often leading to an increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria and a decrease in beneficial species like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. These changes can contribute to gut dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, and inflammation, all of which have been linked to chronic issues, such as cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and weakened immune function.

Changes in the gut microbiome are inevitable due to physiological shifts that occur with aging. Chronic stress can lead to inflammation, weakening the gut lining and altering the microbiome, which allows toxins to enter the bloodstream and further impair immune function. To support gut health and overall well-being, lifestyle recommendations include regular physical activity, stress management through prioritization and relaxation techniques, and adequate sleep.

As we age, there are several pillars that can help balance our gut microbiome and contribute towards healthy aging.

Diet

Diet remains a key player in shaping the gut microbiome, even as we age. A fiber-rich diet with diverse plant-based foods, fermented foods, antioxidants, and polyphenols supports beneficial bacteria. Processed foods, excessive sugar, and artificial additives may promote dysbiosis. Following a Total Gut Balance Diet helps reduce overall inflammation with potent anti-inflammatory foods rich in vitamins, minerals, prebiotic fiber, and resistant starches while enhancing beneficial bacteria and fungi in the gut.7

Physical Activity

Regular physical activity and exercise have been shown to increase microbial diversity and promote beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, which helps maintain gut barrier function. Both aerobic and resistance training can positively influence gut health, helping to counteract age-related microbiome decline.

Keep in mind, however, that more is not better! During extreme exercise, blood gets diverted away from the gastrointestinal system and goes to the heart, lungs, and muscles. Homeostasis in the gut gets disrupted and intestinal cells may also experience damage.8

Sleep

Good quantity and quality sleep is essential to maintain a healthy gut balance. Poor sleep or irregular sleep patterns can negatively impact the gut microbiome by increasing inflammation and disrupting the balance of beneficial bacteria.9 The National Sleep Foundation recommends building and maintaining a consistent sleep routine and schedule (7-9 hours of quality sleep).10

For more tips on how to improve your sleep, explore our 11 sleep optimization strategies in The Sleep Issue of the Eudēmonia Newsletter.

Stress

Chronic stress negatively affects the gut microbiome by increasing gut permeability and altering bacterial composition via the gut-brain axis. Stress management strategies such as meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness can help regulate gut function and support a balanced microbiome.

Social Connections

Social engagement and strong social connections have been linked to better gut health, possibly through effects on stress reduction and immune function. Loneliness and social isolation, on the other hand, have been associated with increased inflammation and microbiome imbalances.11

While aging naturally alters the gut microbiome, maintaining a healthy gut microbiome is a cornerstone of longevity and overall healthy aging. Our gut microbiome thrives on a balanced lifestyle, on which it can reduce the risk of gut dysbiosis, ultimately promoting better digestion, immune function, and overall well-being.

UP NEXT: LET’S TALK ABOUT SEX (SERIOUSLY)

When was the last time you heard someone talk about sexual health in terms of joy? Or aliveness? Or human flourishing? The conversation about sexual health needs an upgrade beyond old stigmas and limited thinking toward a more expansive, life-affirming understanding of sexual well-being.

In the next issue, we explore Juliana Hauser’s incredible talk from the first Eudēmonia Summit. She helped attendees understand why sexual health isn't just about pleasure; it's about creating the conditions for a long, vibrant life.

HUNGRY FOR MORE?

There’s no shortage of fascinating articles, stories, and studies coming out in health and wellness every week. Here are 5 of our recent favorite finds.

01. Exercise might be a key to Alzheimer’s Disease prevention.

02. Scientists may have discovered a natural alternative to Ozempic.

03. Dr. Becky Kennedy (Good Inside) on Huberman’s podcast going DEEP on parenting.

04. Dr. Mark Hyman wants to look at your poop.

05. Japanese purple sweet potato rice recipe: longevity in a rice cooker.

- Lindgren T, Runeson R, Wahlstedt K, Wieslander G, Dammström BG, Norbäck D. Digestive functional symptoms among commercial pilots in relation to diet, insomnia, and lifestyle factors. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2012 Sep;83(9):872-8. doi: 10.3357/asem.3309.2012. PMID: 22946351.

- Foster, J.A., L. Rinaman, and J.F. Cryan, Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 2017. 7: p. 124-136.

- Jacobs, C., et al., Dysmotility and proton pump inhibitor use are independent risk factors for small intestinal bacterial and/or fungal overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013. 37(11): p. 1103-11.

- Ghannoum M. Cooperative Evolutionary Strategy between the Bacteriome and Mycobiome. mBio. 2016 Nov 15;7(6):e01951-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01951-16. PMID: 27935844; PMCID: PMC5111414.

- Gandhi, A., et al., Methane positive small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes, 2021. 13(1): p. 1933313.

- Ghannoum, M.A., et al., A Probiotic Amylase Blend Positively Impacts Gut Microbiota Modulation in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Life, 2024. 14(7): p. 824.

- Ghannoum, M., et al., Effect of Mycobiome diet on Gut Fungal and Bacterial Communities of Healthy Adults. J Prob Health, 2020 8(215).

- O'Sullivan O, Cronin O, Clarke SF, Murphy EF, Molloy MG, Shanahan F, Cotter PD. Exercise and the microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(2):131-6. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1011875. Epub 2015 Mar 24. PMID: 25800089; PMCID: PMC4615660.

- Tanaka A, Sanada K, Miyaho K, Tachibana T, Kurokawa S, Ishii C, Noda Y, Nakajima S, Fukuda S, Mimura M, Kishimoto T, Iwanami A. The relationship between sleep, gut microbiota, and metabolome in patients with depression and anxiety: A secondary analysis of the observational study. PLoS One. 2023 Dec 20;18(12):e0296047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296047. PMID: 38117827; PMCID: PMC10732403.

- National Sleep Foundation. How Much Sleep Do You Really Need? 2020; Available from: https://www.thensf.org/how-

many-hours-of-sleep-do-you- really-need/. - Sherwin E, Bordenstein SR, Quinn JL, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota and the social brain. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366(6465):eaar2016. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2016. PMID: 31672864.

February 20, 2026

February 14, 2026

February 6, 2026

January 31, 2026

January 23, 2026

January 16, 2026

January 9, 2026