Last week, we went deep into creatine, looked at all the data and research, and explained why it’s not just for body builders. Creatine is one of the most studied supplements on earth. The evidence suggests it doesn’t only support strength and muscle recovery; it also improves cognitive performance and mental resilience, especially as we age.

This was a popular issue of the Eudēmonia Newsletter. We got more audience questions than ever before. Turns out many of you are curious about this powerful little supplement. We tried to answer as many of them in the newsletter as we could. But what we didn’t cover, we brought to someone who works at the molecular level.

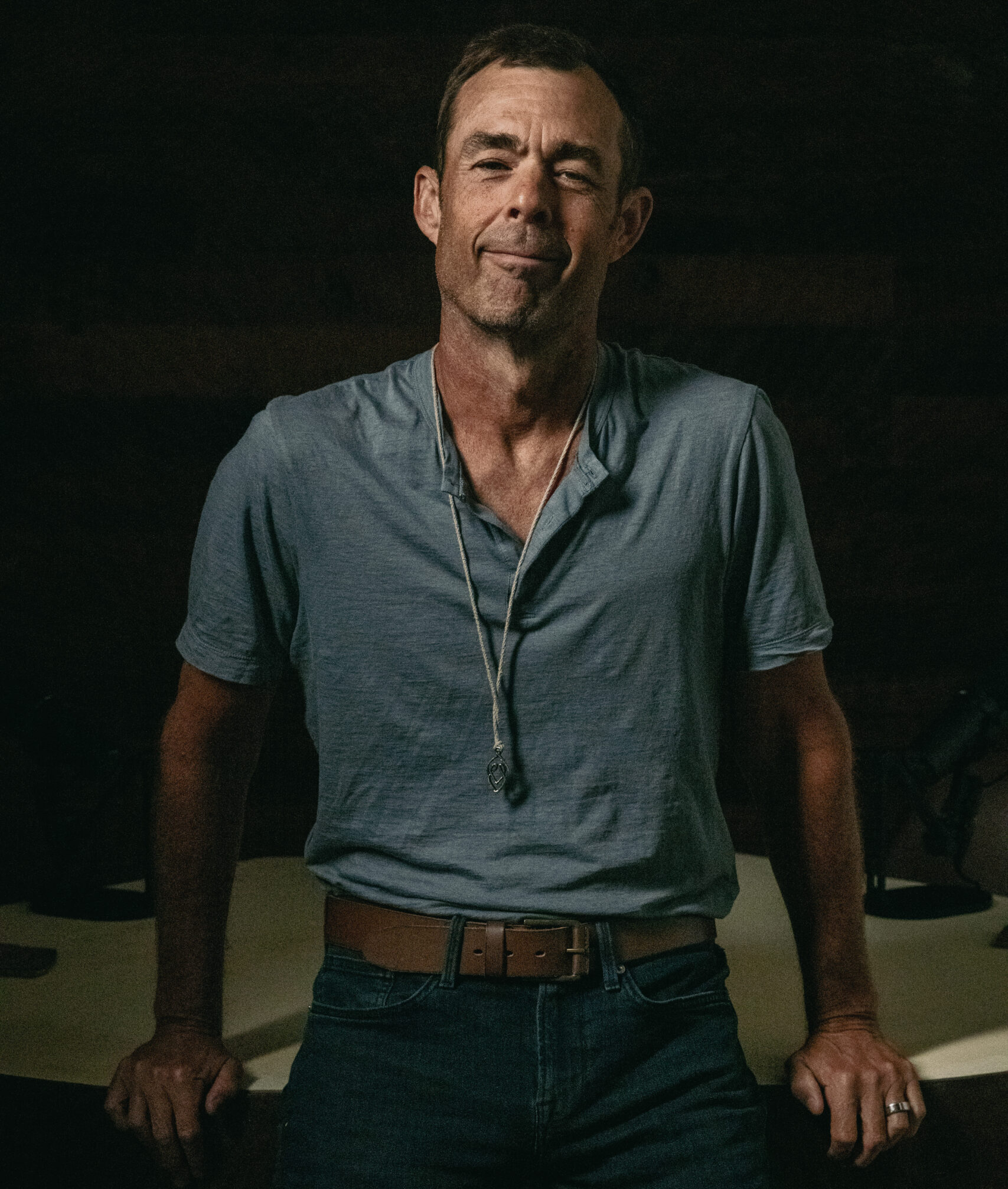

Today, we’re featuring Nick Andrews, a biochemical engineer and pharmaceutical biotech veteran with two decades of experience working directly with cellular energy systems, amino acid pathways, and compound delivery. His background sits at the intersection of biochemistry, pharmacology, and real world application, which makes him uniquely suited to talk about how compounds like creatine actually behave inside the body.

Nick is the founder or cofounder of multiple science-driven health companies, including Push Patch, which uses electro-driven iontophoresis for NAD+ and peptides, and Entera Skincare, a clinician-grade topical line focused on peptide cosmeceuticals. Across these ventures, his work has centered on energy metabolism, cellular transport, and improving how biologically active compounds are absorbed and utilized.

In other words, he doesn’t just study supplements. He studies how molecules move, how cells use energy, and why delivery and dosage matter.

In this Q&A, Nick answers some of your most interesting questions about creatine and offers his perspective on what’s generally misunderstood about the supplement.

But first, he has some context to share.

Creatine: Dose, Timing, and What It’s Really Doing

Creatine is often framed as a muscle supplement. That description is technically correct but incomplete. Creatine is better understood as a cellular energy buffer. Its primary role is to help cells maintain ATP availability when energy demand rises faster than mitochondria can respond.

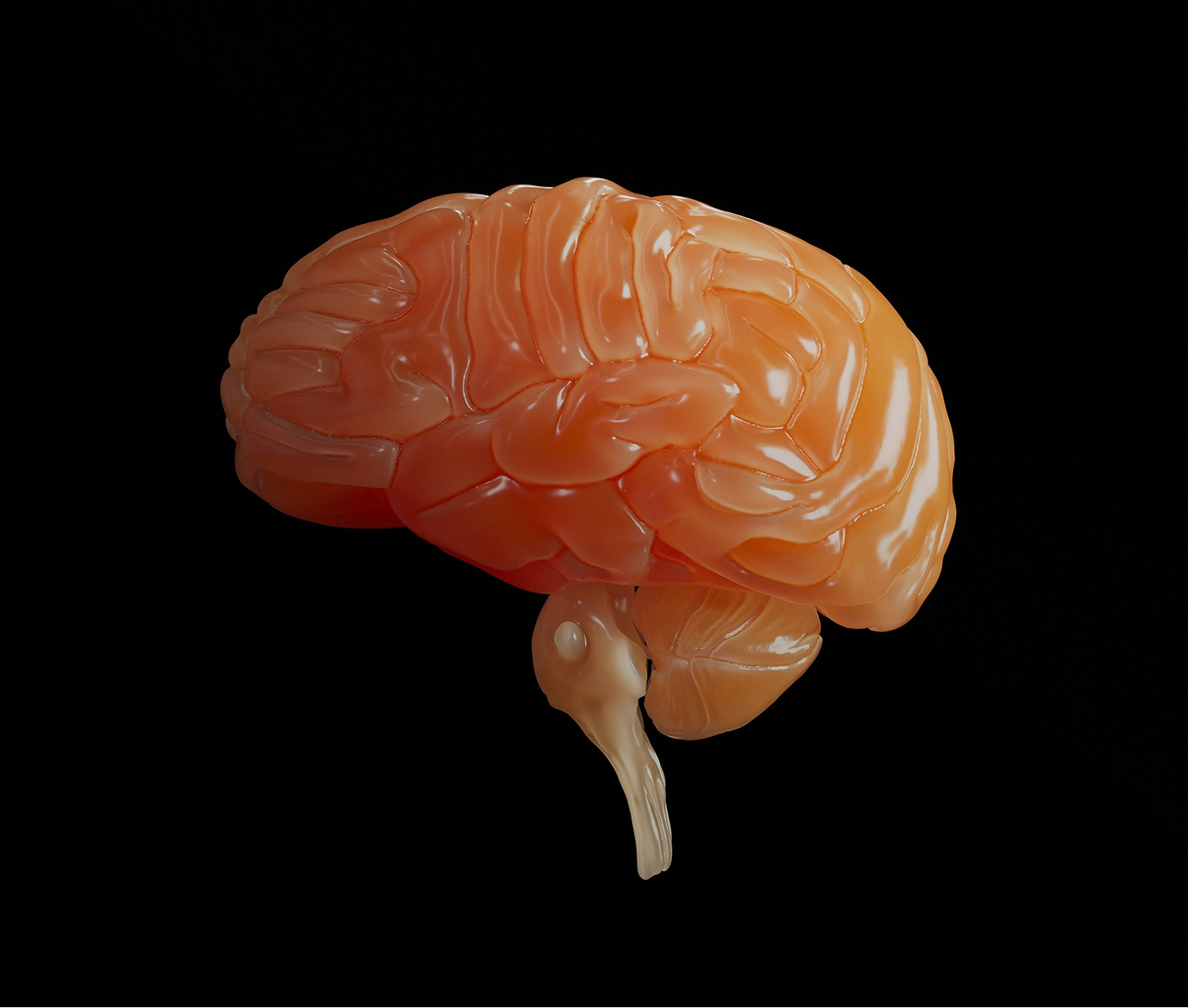

Muscle is one expression of this system. The brain is another.

Once you understand that distinction, most of the confusion around dosing, timing, water retention, and safety falls away.

Creatine and ATP Availability

ATP is constantly being consumed. In both muscle and brain tissue, there are moments where demand spikes abruptly. When that happens, ATP levels can fall faster than mitochondria can regenerate it. Creatine exists to smooth that gap.

Inside cells, creatine is stored largely as phosphocreatine. When ATP is spent and converted to ADP, phosphocreatine donates a phosphate group, rapidly regenerating ATP through the creatine kinase system. This process does not create energy. It preserves function during high turnover.

That buffering capacity is why creatine improves repeated muscular output, but it is also why creatine has been studied in neurological contexts. Neurons are energetically demanding cells with limited tolerance for shortfalls. Increasing the size of the creatine and phosphocreatine pool increases energetic resilience

Two Different Dosing Conversations

Most public discussion treats creatine as if there were only one correct dose. In practice, there are two distinct dosing conversations that serve different goals.

For muscle and general performance, creatine works by saturating muscle stores. Most people reach near-maximal saturation with 3–5 grams per day taken consistently over several weeks. Some choose a short loading phase of around 20 grams per day for 5–7 days to reach saturation more quickly, followed by a lower maintenance dose. Once muscle stores are full, additional creatine does not increase storage. Excess is filtered and excreted.

There is a separate, less commonly discussed dosing range that appears in neurological and high-demand research contexts. In those settings, daily intakes in the range of 10–20 grams are often used, sometimes for extended periods. The goal here is not muscle saturation. It is to increase the availability of creatine and phosphocreatine in brain tissue.

Brain uptake is regulated and slower than muscle uptake. Higher intake is used to increase exposure over time and create a sufficient gradient to meaningfully shift neural energy buffering. This is why higher doses appear in neurological literature without contradicting the lower doses used for muscle.

Understanding this distinction is critical. Ten to twenty grams per day is not “more muscle creatine.” It is a different application entirely.

Q. Recently I experimented with taking 30g creatine daily, spread into 2–3 doses across the day. I grew wary of potential liver/ kidney issues so have since discontinued high dosing, going back to 5g daily in food. What are your thoughts on high dose creatine, and would there be any scenarios where you'd need to be careful about liver or kidney issues

Creatine itself is not toxic to the liver or kidneys. The concern with higher doses is not organ damage in healthy individuals, but total creatine turnover and how lab markers are interpreted.

When intake increases, more creatine is converted into creatinine as part of normal metabolism. That can raise serum creatinine without representing kidney injury. In healthy kidneys, filtration simply scales. The system adapts.

Thirty grams per day is higher than what is typically required, even for neurologic intent. Most research-driven high-dose contexts cluster closer to 10–20 grams per day. Beyond that range, additional intake tends to increase excretion rather than tissue availability.

Scenarios where caution is appropriate are those where renal reserve or fluid regulation is already constrained. That includes known kidney disease, reduced filtration capacity, chronic dehydration, uncontrolled hypertension, heavy NSAID use, or stacking very high protein intake on top of very high creatine intake. In those cases, the issue is cumulative renal load and interpretation, not creatine acting as a toxin.

For healthy individuals, routine liver testing is unnecessary. Kidney testing only becomes relevant if there is pre-existing risk or symptoms. Your instinct to step back from thirty grams is reasonable, not because it is dangerous, but because it is usually unnecessary.

Q. Is timing important when taking creatine? Does it matter whether the dose is taken all at once or split throughout the day?

Creatine is a saturation compound. Once intracellular stores are full, timing has very little impact.

Splitting doses does not make creatine work better. It makes higher intakes easier to tolerate. At 3–5 grams per day, once-daily dosing is sufficient. At 10–20 grams per day, splitting the dose across the day reduces gastrointestinal stress and improves comfort.

Post-workout timing can slightly enhance uptake when paired with carbohydrates or protein, but the effect is modest. Consistency over weeks matters far more than clock precision.

Q. Some forms of creatine, such as creatine HCL, claim to avoid the water retention associated with creatine monohydrate. Do these alternatives work just as well?

All effective creatine increases intracellular water. That is part of its mechanism, not a side effect to avoid.

Water drawn into muscle cells improves force production, cellular signaling, and resilience under stress. What people often describe as “water retention” is either transient scale weight during loading or gastrointestinal bloating, which is a tolerance issue, not a cellular one.

Creatine HCL dissolves easily and may feel gentler for some people’s digestion. That can be useful. But gram for gram, creatine monohydrate remains the benchmark for effectiveness, cost, and depth of evidence. Claims about avoiding water retention usually reflect lower delivered creatine or less aggressive dosing, not a fundamentally different biological effect.

Q. Are there signs or signals from your body that indicate your creatine dose is higher than what you need or tolerate well? How do you know if you're taking too much (or too little)?

Creatine tends to give clear feedback when it is mismatched to the individual.

When the dose is higher than needed, common signals include persistent gastrointestinal discomfort, cramping that resolves with dose reduction, excessive thirst without improved hydration status, or a sense of fullness without meaningful performance or recovery benefit.

When the dose is too low or ineffective, there is typically no change in repeated-effort capacity, recovery tolerance, or resilience after several weeks of consistent use. Some people begin closer to saturation due to diet or genetics and notice smaller visible changes regardless of dose.

Creatine is not a “push harder” compound. It is a “match capacity to demand” compound.

Q. For someone who tends to run a bit dehydrated (even when they’re drinking plenty of water), does that change how they should think about taking creatine? Is daily use still fine, or would a lower frequency make more sense?

Creatine does not cause dehydration, but it does increase intracellular water demand. If someone already struggles with fluid or electrolyte balance, creatine can expose that weakness.

In practice, sodium and overall electrolyte intake matter as much as water volume. Many people who feel “chronically dehydrated” are actually under-salted or under-electrolyted. Splitting doses can reduce osmotic stress in the gut, and pairing creatine with adequate electrolytes improves tolerance.

Daily use remains appropriate. Lower frequency is usually unnecessary unless creatine is being used as an occasional tool rather than a saturation strategy. Additionally you can utilize the approach I do. I purchase a stand alone electrolyte mix and add a scoop of electrolyte mix along with creatine. This ensures sufficient electrolytes are available.

Disclaimer: This newsletter is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute providing medical advice or professional services. The information provided should not be used for diagnosing or treating a health problem or disease, and those seeking personal medical advice should consult with a licensed physician.

March 6, 2026

February 28, 2026

February 21, 2026

February 14, 2026

February 7, 2026

January 23, 2026

January 16, 2026

January 16, 2026